Sexual Trauma, Suicide, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among the Asexual Adult Population: An Analysis of the 2020 Ace Community Census

Abstract

Objectives: To quantify the prevalence of sexual trauma and its respective types, suicidal ideation, and PTSD diagnosis among asexual adults in an online community.

Methods: A secondary data analysis was conducted among asexual adults from the 2020 Ace Community Census (n = 7,217). Sexual trauma prevalence, PTSD diagnosis, and suicidal ideation prevalence were determined.

Results: The prevalence of sexual trauma victims was 63.5%. Female, asexual adults were most likely to be victims (48.1%), while each gender reported similar professional PTSD diagnosis (range 7.3% - 7.7%). PTSD prevalence was 9.6% among sexual trauma victims. Suicidal thoughts, planning, and attempts were reported more frequently among sexual trauma victims.

Conclusions: Sexual trauma, PTSD, are suicide are problems among asexual adults. Improved dialogue and trust between healthcare providers and asexual individuals is critical for early identification and treatment.

Index Words: Non-consensual, rape, mental health, violence, victims

INTRODUCTION

Asexuality is generally defined as lack of sexual attraction to anyone (Bogaert, 2004; Decker, 2015; Yule, Brotto, & Gozalka, 2015). The Asexuality and Visibility Education Network (AVEN), an online community for self-identified asexual individuals, states “Many asexual people may experience forms of attraction that can be romantic, aesthetic, or sensual in nature but do not lead to a need to act out on that attraction sexually. Instead, we may get fulfillment from relationships without sex, but based on other types of attraction” (Asexuality and Visibility Education Network [AVEN], 2021). As asexuality definitions vary (Jones & Hayter, 2017), so does the estimated prevalence of asexual individuals, ranging from to 0.3% to 1.05% of men and 0.3% to 0.5% of women in the United Kingdom (Aicken, Mercer, & Cassell, 2013).

Asexual individuals often face misconceptions about their orientation, which may put them at risk of their health issues being ignored or misunderstood. Since asexual individuals may face similar social stigma to that experienced by homosexual and bisexual individuals, in that they may also experience discrimination and/or marginalization, it is possible asexual individuals may experience higher rates of psychiatric disturbance compared to those considered sexual (Yule, Brotto, & Gozalka, 2013). Asexual individuals may experience additional stigma because they experience a lack of sexual attraction in a culture arguably dominated by sexuality (Yule, Brotto, & Gozalka, 2013).

The associations between sexual trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among asexual individuals are not well-studied. A published study (Parent & Ferriter, 2018) indicated asexual individuals were more likely to report receiving a PTSD diagnosis and sexual trauma within the past twelve months, compared to non-asexual individuals. However, this research was limited to college students within the United States and included a relatively small number of asexual individuals (n=228).

Asexual individuals may be more likely than non-asexual individuals to recognize sexual aggression as sexual assault (MacNeela & Murphy, 2015). This potentially heightened awareness emphasizes post-trauma communication with healthcare providers to treat the subsequent trauma. There are complexities in assessing sexual experience types by self-report for reasons including, but not limited to, inconsistent definitions of “consent” and the relationship between verbal coercion and consent (Pugh & Becker, 2018). Sexual violence is a concept not easily measured, primarily due to inconsistent definitions of sexual assault and rape (Office for Victims of Crime, 2018).

Some gender minority individuals, including transgender and genderqueer, have reported higher depression rates, suicidal ideation, and attempts, relative to cisgender peers (Horwitz et al., 2020). Among sexual minorities, those identifying as pansexual, bisexual, and queer reported more suicidal risk factors compared to heterosexual individuals (Horwitz et al., 2020). Similarly, non-heterosexual cis men, non-heterosexual cis women, transgender, and non-binary individuals had higher lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide, compared with males and females (Witte, Kramper, Carmichael, Chaddock, & Gorczyca, 2020).

In this study, rather than use the term “assault”, “trauma” was used and reported by each type. The purpose of this research was to quantify and analyze the prevalence of sexual trauma and its respective types, suicidal ideation, and receipt of PTSD diagnosis among asexual individuals in an online, asexual community. The hypotheses are that asexual individuals are victims of sexual trauma, and those victims are more likely to have suicidal ideations and have been diagnosed with PTSD, than non-victims.

METHODS

A secondary data analysis of the 2020 Ace Community Census was conducted, with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the University of Toledo. Ace is a shorthand term for asexual. The census was an online survey of 123 questions, an annual research project completed by the AVEN Survey Team (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

The census represents a convenience sample recruited via snowballing sampling techniques. Announcements containing a survey link were posted on several asexual websites, including but not limited to, AVEN, The Asexual Agenda, and asexuality-themed groups on various social networking sites, including but not limited to, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, Reddit, and Livejournal (AVEN Survey Team, 2020b). Respondents were encouraged to share the link with other asexual communities.

Since the Ace Community Census is not affiliated with any university or formal research organization, there was no formal IRB approval process (AVEN Survey Team, 2020b). However, the instructions on the first page of the Census state, “All data collected will be kept confidential, and no identifying information will be collected. Please note that some data may be shared with individuals at academic or community non-profit institutions who request information from the survey team to publish information about the identities, health, and health needs of ace communities. All data requests will be reviewed by the survey team. Taking part in this survey is completely voluntary and you can stop the survey at any time. Most questions in the survey are completely optional, and can be left blank if you are uncomfortable or do not know how to answer.” (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

Additional instructions on the first page discuss the sensitive topics covered in the survey and that if someone finds the questions uncomfortable, they do not need to answer them. Further resources (phone numbers and websites) for the National Sexual Assault Hotline, National LGBT+ Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence Helpline, Rape Crisis National Telephone Helpline, and the Ending Violence Canada Association are provided following the sexual trauma questions (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

Asexual Identity

Asexual identity was obtained through the question, “Which of the following labels do you most closely identify with?” followed by the options of asexual, gray-asexual, demisexual, questioning if asexual/gray-asexual/demisexual, or other. For this study, only those who identified as “asexual” and were eighteen years of age or older were included (n = 7,217).

Sexual Trauma

The Sexual Violence section of the survey included ten questions, each allowing the respondent to answer how many individuals had inflicted upon them a particular trauma. The questions were analyzed as aggregates pertaining to a specific violence type (rape, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact) (Table 1) as defined by the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) (NISVS, 2015). Two questions pertained to unwanted sexual contact, three questions to rape, and four questions to sexual coercion (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a). One question, “How many people have verbally harassed you while you were in a public place in a way that made you feel unsafe?” did not fit a category and was therefore excluded.

Survey respondents were classified as “ever assaulted” if they answered at least one person traumatized them. Survey respondents were further classified as “ever raped”, “ever coerced”, and “ever contacted” if they answered at least one person traumatized them in those respective trauma types.

The NISVS defines “rape” as “any completed or attempted unwanted vaginal (for women), oral, or anal penetration through the use of physical force (such as being pinned or held down, or by the use of violence) or threats to physically harm and includes times when the victim was drunk, high, drugged, or passed out and unable to consent.” (NISVS, 2015). This aligns with the questions, “How many people have ever used force or threats of physical harm to try to make you have vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex, or put fingers or an object into your vagina or anus, but it *did not* happen?” and “How many people have ever had vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex with you, or put fingers or an object into your vagina or anus in the following circumstances:” “when you were drunk, high, or passed out and unable to consent?” and “when using force or threats to physically harm you?” (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

The NISVS defines “coercion” as “unwanted sexual penetration that occurs after a person is pressured in a non-physical way”, including “unwanted vaginal, oral, or anal sex after being pressured in ways that included being worn down by someone who repeatedly asked for sex or showed they were unhappy; feeling pressured by being lied to, being told promises that were untrue, having someone threaten to end a relationship or spread rumors; and sexual pressure due to someone using their influence or authority.” (NISVS, 2015).

The four questions in the census were, “How many people have ever had vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex with you, or put fingers or an object into your vagina or anus in the following circumstances: “after they pressured you by telling you lies, or making promises about the future that they knew were untrue?”, “after they pressured you by threatening to end your relationship or threatening to spread rumors about you?”, “after they pressured you by wearing you down by repeatedly asking for sex or showing they were unhappy?”, and “after they pressured you by using their influence or authority over you, for example a boss or a teacher?” (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

The NISVS defines “unwanted sexual contact” as “unwanted sexual experiences involving touch but not sexual penetration, such as being kissed in a sexual way, or having sexual body parts fondled, groped, or grabbed.” (NISVS, 2015). The following two questions were used to analyze this sexual trauma type. “How many people have ever exposed their sexual body parts, made you show your sexual body parts, or made you look at sexual photos or movies when you did not want it to happen?” and “How many people have ever kissed you in a sexual way, fondled, groped, grabbed or touched you when you did not want it to happen or in a way that made you feel unsafe?” (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

PTSD

PTSD was assessed by the question, “Have any of the following ever applied to you?” PTSD was an included condition, followed by the options, yes – professionally diagnosed, yes – self-diagnosed, unsure, and no. Only respondents indicating “yes – professionally diagnosed” were considered to have PTSD.

Gender Identity

Gender information was obtained through the question, “Which of the following best describes your gender identity? (check all that apply)”, followed by the options of man or male, woman or female, non-binary, agender, androgynous, bigender, demigirl, demiguy, genderfluid, genderqueer, neutrois, no gender, questioning or unsure, and other (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a). For analysis simplification, those who responded other than male or female only were combined into one category, “non-gender”. There was a separate question in the Census, “Do you identify as transgender?”, followed by the options of yes, no, unsure, and prefer not to answer (AVEN Survey Team, 2020a).

Statistical Analyses

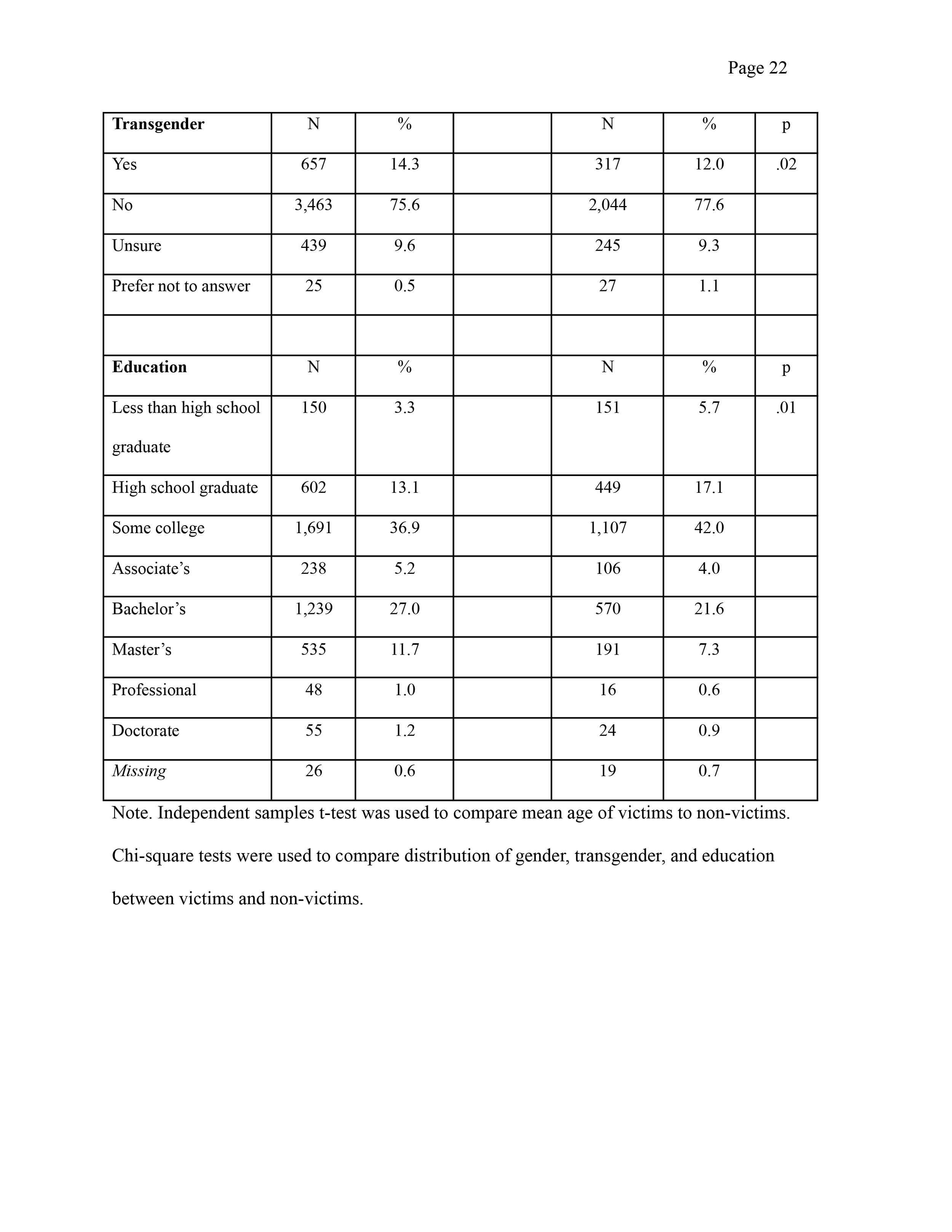

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for the data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the prevalence and distribution of sexual trauma and its respective types, suicide, and receipt of PTSD diagnosis. An independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean age of sexual trauma victims to non-victims. Chi-square analyses were used to compare demographics between sexual trauma victims and non-victims, the proportions of asexual individuals by gender for each sexual trauma type and PTSD diagnosis, and PTSD and suicidal ideation prevalence between sexual trauma victims and non-victims.

RESULTS

Among this online, asexual community, 3,391 identified as woman or female (47.0%), 795 (11.0%) identifying as man or male, 3,029 did not identify with a gender (42.0%), and two individuals did not answer. Out of the 7,217 asexual individuals, 974 (13.5%) also identified as transgender and fifty-two individuals did not answer (chi-square = 22.09, df = 2, p = 0.01). (Table 2). In total, asexual individuals from eighty-eight different countries completed the census.

Sexual Trauma

There was a statistically significant difference in age between victims (mean = 25.21) and non-victims (mean = 23.24) (t = 13.18, df = 5,983, p = .01, Cohen’s d = 0.313) (Table 2). Women were most likely (n = 2,204, 48.1%) to self-report as sexual trauma victims (chi-square = 29.67, df = 2, p = .01) (Table 2).

Types of Sexual Trauma

Women were most likely to report all sexual trauma types (Table 2). This includes rape (50.7%) (chi-square = 7.97, df = 2, p = .019), coercion (50.3%) (chi-square = 10.01, df = 2, p =0.01), and unwanted sexual contact (48.2%) (chi-square = 22.24, df = 2, p = .01).

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Women were more likely to have been professionally diagnosed with PTSD (47.6%) compared to those do not identify with a particular gender (41.8%), and men (11.1%). There were 530 (252 females, 59 males, and 219 non-gender identified) sexual trauma victims who reported a PTSD diagnosis (chi-square = 90.37, df = 1, p = .01) (Table 3).

PTSD diagnosis is higher among those who have ever been sexually assaulted (9.8%) compared to non-victims (3.6%) (Table 3) Additionally, PTSD diagnosis was more than five times as likely among rape victims, four times as likely among sexual coercion victims, and three times as likely among unwanted sexual contact victims (Table 3).

Suicide

A higher proportion of sexual trauma victims, at some point in their lives, seriously thought about trying to kill themselves (60.4%), made plans to kill themselves (30.9%), and tried to kill themselves (14.6%), compared to non-victims (46.2%, 19.8%, and 7.0%, respectively). (Table 4)

DISCUSSION

In this study, a substantial proportion of asexual individuals reported experiencing sexual trauma, suicidal ideation, and PTSD diagnosis. Both PTSD and suicidal ideation (thoughts, planning, and attempting) were all reported more frequently by sexual trauma victims. Though it is unknown whether PTSD diagnosis and suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts preceded or followed sexual trauma, the results demonstrate the importance of asexual individuals being able to access and communicate with healthcare providers regarding their physical and mental health.

Asexual individuals identifying as female were most likely to experience sexual trauma and PTSD compared to all other genders. Among asexual individuals who were sexual trauma victims, 11.5% (530 out of 4,584) self-reported receiving a PTSD diagnosis. This proportion is greater than the 3.5% of asexual individuals who were sexual assault victims that self-reported a PTSD diagnosis (Parent, 2018). The gender-specific prevalence of self-reported PTSD diagnosis is greater than that reported in the 2007 National Comorbidity Survey (5.2% for adult females and 1.8% for adult males) (Harvard Medical School, 2007). However, these figures are based on the entire sample, not restricted to sexual trauma victims. In this study, 7.3% of asexual individuals self-reported a PTSD diagnosis, double the 3.6% past-year prevalence of PTSD among adults (Harvard Medical School, 2007).

The proportion of females who reported experiencing sex they did not consent to or were unable to consent to (50.7%) is higher than the lifetime risk of 20.0% experiencing completed or attempted rape (NISVS, 2015). Asexual individuals may report they are sometimes pressured to date or have sexual contact because others perceive their lack of interest as suggesting they have not yet found the right person or need to have a good sexual experience (AVEN Survey Team, (2020b; Decker, 2015). Cultural norms around male interest in sex may help explain why more males in this study reported non-consensual sex (11.7%) compared to the NISVS (7.1%) (NISVS, 2015).

Females also reported having sex because of coercion (50.3%) more frequently than the lifetime risk of 16% (NISVS, 2015). Further, females were most likely to report non-consensual sexual contact (48.2%), greater than the lifetime risk of reporting unwanted sexual contact among all women (37.0%) (NISVS, 2015). Based on the data from this research, healthcare providers need to establish open, honest communication with their asexual patients, particularly those who identify as female, to best treat their needs.

A proportion of transgender individuals (9.1%) reported having experienced sexual assault. This is important because in a study of sexual victimization and subsequent police reporting by gender identity among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults, transgender individuals reported having experienced sexual assault and rape more than twice as frequently as cisgender LGBQ individuals (Langenderfer-Magruder, Walls, Kattari, Wittfield, & Ramos, 2016). Similarly, the 2015 United States Transgender Survey, which was completed by 27,715 individuals (of whom 10% identified as “asexual”), indicated that 10% of transgender individuals were sexually assaulted in the year prior to survey completion and 47% were sexually assaulted at some point in their lifetime (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). These data provide additional evidence that transgender, asexual individuals must also be able to access and communicate with healthcare providers.

A systemized review of articles identified six categories of good doctors, including general interpersonal qualities, communication and patient involvement, ethics, medical management, and medical competence (Steiner-Hofbauer, Schrank, & Holzinger, 2018). The prevalence of sexual trauma victims, suicidal ideation, and PTSD among asexual individuals is a call to action for healthcare providers and public health professionals. There is a need for education and awareness to providers and the public regarding the asexual orientation. Well-informed healthcare providers will foster a trusting environment where patient-provider communication can be open, honest, and free from judgement and disdain. The needs for asexual individuals, identifying of any gender, to access and obtain quality healthcare are no different than anyone else.

Trust between patient and healthcare provider is essential. Healthcare providers who understand what it means when patients identify as asexual, and respect them for who they are, can greatly improve their experience in the healthcare setting (Jones & Hayter, 2017). There are individuals whose asexuality is still dismissed by providers (Foster & Scherrer, 2014). Thus, sexual trauma and the resulting mental anguish may be ignored and thus, not disclosed by the patient, delaying treatment and impairing their health and well-being. As with any other health issue, early identification and treatment means better prognosis.

Sexual minority groups, usually referring to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, may face barriers in accessing appropriate healthcare (Dahl, Fylkesnes, Sorlie, & Malterud, 2012; Davy & Siriwardena, 2012; Jones & Hayter, 2017; Shields et al., 2012). Communication between healthcare providers and their patients is paramount for optimal treatment (Jones & Hayter, 2017). Improved understanding of sexual trauma history and mental health, including suicidal ideation and PTSD, among asexual patients is necessary for their health and well-being and enhancing efforts to recognize the existence of the asexual identity.

It has been suggested that asexual identity may facilitate greater exploration and self-reflection, potentially leading to recognition that prior sexual experiences were assault (MacNeela & Murphy, 2015). Others have posited that for some who identify as asexual, sexual trauma history may influence their identification as asexual. This suggests victims may intentionally adopt an asexual identity to avoid discussing their sexual trauma history and/or avoid sexual behavior due to prior sexual trauma (Leiblum & Wiegel, 2002; Parent & Ferriter, 2018; Rosen, 2000).

Though sexual trauma may be associated with aversion to sexual behavior (Leiblum & Wiegel, 2002; Rosen, 2000), suggesting that asexual orientation is the result of a prior trauma may contribute to the misconception that asexual individuals are simply sex-repulsed or sex-avoidant, implying that asexuality is more behavioral rather than an orientation. Common themes of the coming out process for asexual individuals include skepticism from family and friends, lack of acceptance and misunderstanding, and non-disclosure of asexual identity (Robbins, Low, & Query, 2016). The aforementioned speculation perpetuates these themes.

Though the data were provided by online survey, participant ages ranged from 18 to 84 years. Additionally, there is no data source that approaches the sample size of self-identifying asexual individuals provided by the 2020 Ace Community Census - completed by 7,217 adults from eighty-eight countries. The purpose of this study was descriptive in nature, to determine sexual trauma prevalence and its respective types, suicidal ideation, and receipt of PTSD diagnosis among asexual individuals from an online community.

Limitations

Snowball sampling is a useful strategy when the potential study population is hard-to-reach, such as asexual individuals. However, since snowball sampling does not select units for inclusion in the sample based on random selection, unlike probability sampling techniques, it is impossible to determine possible sampling error and makes statistical inference testing difficult (Crossman, 2019). The data is not population-based, but rather from an online community. Therefore, the sample may not represent the asexual population.

These data relied on self-report of a PTSD diagnosis. There is no way of definitively knowing if prior sexual trauma contributed to the diagnosis nor if the diagnosis occurred before or after the sexual trauma. Those with PTSD symptoms may not recognize them and, therefore, may not visit a healthcare provider. It is possible participants may have been diagnosed with PTSD but not had the diagnosis communicated to them, they may misremember diagnoses, and may rely on Internet tests of questionable validity to self-diagnose. Medical record access to determine a physician diagnosis would be the best validation method. It was impossible to detect the reason(s) for PTSD onset. Future research may use the Life Events Checklist (Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004) to separate individuals with sexual trauma history from those who may have PTSD arising from other events.

Those who experienced sexual trauma, especially from an intimate partner, may not label it as such. Thus, sexual trauma histories are limited by wording and question content and make one speculate if the questions in the census fully captured the range of sexual trauma and its manifestations, and not refer to the same behavior across different questions. Though the questions appear to align with the NISVS definitions, there was no indication they were used to draft the questions (AVEN Survey Team, 2020b). More questions on this topic may be necessary in future studies.

The sexual trauma could have occurred at any time, as the questions did not pertain to a specific time period. Further, we do not know if victims had been sexually traumatized multiple times in their lives. Reaching a consensus on defining and evaluating issues such as verbal sexual coercion and consent, key aspects to sexual trauma, will help researchers better understand these issues and suggest methods for prevention (Pugh & Becker, 2018).

Public Health Implications

These findings indicate that asexual individuals are victims of sexual trauma, mental anguish and suffering, which includes but is not limited to suicidal ideation and PTSD. The asexual population is still striving for acceptance in the LGBTQ+ population, with healthcare providers, and the general public. An inclusive healthcare environment may help asexual individuals must be empowered to seek medical care in the event of an assault. Asexual education and awareness for healthcare providers could help asexual individuals be more willing to seek care, increase patient-provider dialogue, and improve treatment of asexual patients.

References

Aicken, C.R.H., Mercer C.H., & Cassell, J.A. (2013). Who reports absence of sexual attraction in Britain? Evidence from national probability surveys. Psychology and Sexuality, 4, 121–135.

Asexuality and Visibility Education Network Survey Team. (2020). 2020 Ace Community Census. Retrieved from https://asexualcensus.wordpress.com/past-censuses/.

Asexuality and Visibility Education Network Survey Team. (2020). Guide to the Asexual Community Survey Data. Retrieved from https://asexualcensus.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/dataguide.pdf.

Asexuality and Visibility Education Network. (2021). Overview. Retrieved from https://asexuality.org/?q=overview.html.

Bogaert, A.F. (2004). Asexuality: prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample. The Journal of Sex Research, 41, 279-287.

Crossman, A. What is a snowball sample in sociology? (2019). Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/snowball-sampling-3026730.

Dahl B, Fylkesnes AM, Sorlie V, Malterud K. (2012). Lesbian women’s experiences with healthcare providers in the birthing context: A meta-ethnography. Midwifery, 6, 674-681.

Davy Z, Siriwardena AN. (2012). To be or not to be LGBT in primary care: Health care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. British Journal of General Practice, 62, 491-492.

Decker, J.S. (2015). The invisible orientation: An introduction to asexuality. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing.

Foster, A.B., & Scherrer, K.S. (2014). Asexual-identified clients in clinical settings: implications for culturally competent practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 422-430.

Gray M.J., Litz, B.T., Hsu, J.L., & Lombardo, T.W. (2004). Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment, 11, 330-341.

Harvard Medical School. National Comorbidity Survey. (2007). Retrieved from https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/table_ncsr_12monthprevgenderxage.pdf.

Horwitz, A.G., Berona, J., Busby, D.R., Eisenberg, D., Zheng, K., Pistorello, J., … King, C.A. (2020). Variation in suicide risk among subgroups of sexual and gender minority college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviors, 50, 1041-1053.

Jones, C., Hayter, M., & Jomeen, J. (2017). Understanding asexual identity as a means to facilitate culturally competent care: a systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 3811-3831.

Langenderfer-Magruder, L., Walls, N.E., Kattari, S.K., Whitfield, D.L., & Ramos, D. (2016). Sexual victimization and subsequent police reporting by gender identity among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults. Violence and Victims, 31, 320-331.

Leiblum, S.R., & Wiegel, M. (2020). Psychotherapeutic interventions for treating female sexual dysfunction. World Journal of Urology, 20, 127-136.

MacNeela, P., & Murphy, A. (2015). Freedom, invisibility, and community: a qualitative study of self-identification with asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 799-812.

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2015). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Retrieved from https://www.ustranssurvey.org/reports.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf.

Office for Victims of Crime. (2018). 2018 National Crime Week Victims’ Guide: Crime and Victimization Fact Sheets. Retrieved from

https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_SexualViolence_508_QC.pdf.

Parent, M.C., & Ferriter, K.P. (2018). The co-occurrence of asexuality and self-reported post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and sexual trauma within the past 12 months among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1277-1282.

Pugh, B., & Becker, B. (2018). Exploring definitions and prevalence of verbal sexual coercion and its relationship to consent to unwanted sex: implications for affirmative consent standards on college campuses. Behavioral Sciences, 8, 1-28.

Robbins, N.K., Low, K.G., & Query, A.N. (2016). A qualitative exploration of the “coming out” process for asexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 751-760.

Rosen, R.C. (2000). Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in men and women. Current Psychiatry Reports, 2, 189-195.

Shields L, Zappia T, Blackwood D, Watkins R, Wardrop J, Chapman R. (2012). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender parents seeking healthcare for their children: A systematic review of the literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 9, 200-209.

Steiner-Hofbauer, V., Schrank, B., & Holzinger, A. (2018). What makes a good doctor? Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, 168, 398-405.

Witte, T.K., Kramper, S., Carmichael, K.P., Chaddock, M., & Gorczyca, K. (2020). A survey of negative mental health outcomes, workplace and school climate, and identity disclosure for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, and asexual veterinary professionals and students in the United States and United Kingdom. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 257, 417-431.

Yule, M.A., Brotto, L.A., & Gorzalka, B.B. (2013). Mental health and interpersonal functioning in self-identified asexual men and women. Psychology and Sexuality, 4, 136-151.

Yule, M.A., Brotto, L.A., & Gorzalka, B.B. (2015). A validated measure of no sexual attraction: the asexual identification scale. Psychological Assessment, 27, 148-160.